The idea invaded my mind in the spring of 2013 like a colony of stealthy termites. I hardly knew it was there, yet it ate at me—a relentless occupying force that quickly multiplied and chewed holes in all my summer plans. By June I’d totally lost control and the idea became a full-blown infestation: I would write a book about my mom. I would gather photos, interview everyone, and shape her story, all eighty-five years of it. And I would do it that summer.

It’s an audacious thing to grab hold of another person’s story, but I didn’t know that at the time. All I knew was that Mom seemed to be getting depressed and I wanted to stop that trend. I couldn’t afford to cheer her up with a trip to Paris, or a shopping spree on Las Vegas’s Miracle Mile. All I had to give was my time and my belief that she was truly extraordinary.

At first the book felt like any other project, though infused with more soul than, say, those nifty projects Home Depot expects us to tackle on brisk Saturday mornings with our dapper teen-age sons. I put together a binder with tabs and sheet protectors and compiled a list of interview questions. I planned the book in a predictable fashion—page 1 for title and intro, pages 2–3 for her childhood, 4–5 for early adulthood, and so on. I envisioned it as a yearbook of sorts—lots of photos, with just enough text to tie it together. I’d keep it to thirty-six pages. I had this.

I sent the plan to my four siblings and waited for them to laud my bold initiative and devotion to Mom. I waited for the heady collaboration to begin, the shared purpose, the teamwork. And then I waited some more.

“Would you PLEASE answer my email?” I pleaded in text messages.

After another week, the cringey replies crept in. No one had time for this, who knew where all those photos were, and why couldn’t I just lie on the beach all summer like a normal teacher?

But I was convinced Mom needed this. She’d had a tough life. Her first husband—the love of her life—had died young, leaving her alone with four kids to raise, the oldest nearly five years and the youngest six weeks. Then, after a brief failed marriage to my dad, she was left with this here fifth kid, too. A dozen years later, we were a horde of quarreling teenagers who blasted Black Sabbath and bared our midriffs and failed math class and hurled vases at each other while she was busy working. Then a few more years flew by and we all grew up and left her alone, too.

After she retired from thirty years of teaching elementary school, Mom had a great ten years or so traveling, bowling, and enjoying her grandchildren. But then the quality of her life seemed to head south. Her friends started dying, the Yankees stunk, Obama got elected again, her hair was still frizzy, she’d had to quit smoking, and Hurricane Sandy was a bitch and a half. She was watching Law and Order marathons and speaking in a worrisome, flat tone. (“I bowled a 127 yesterday. My thyroid is low. Remember Mrs. Paoni? She’s dead.”) I worried she would slip away into some sad dementia and then die disappointed, feeling like her life had been meaningless. Suddenly it became inevitable that I would spend the summer sitting on my butt scanning hundreds of photos, exchanging 40,000 emails with my sisters (“Was it you or Theresa whose doll got run over?”), and searching the internet for the Cracker Jacks label from 1933.

Once my siblings accepted the idea of the book, The Great Group Memory Dump began, in a barrage of voicemails, emails, and texts.

“Barb, you have to put in how Mom fell asleep at the typewriter that time and woke up on the floor.”

“Barbie, put in that time we waited for hours to see the Capitol but the whole time Mom thought it was the White House.”

“Hey, Boo-boo—remember Grandma’s story of how Mom painted a green stripe down the side of Uncle Tony’s car when she was little?”

They also sent photos. I’d asked for twelve pictures of each of them, from babyhood to the present, and six of each of their kids. Instead they sent terrible cell-phone snaps of old discolored photos, often with the glare of a flash or the shadow of their own hand in the frame.

After a few weeks I had a list of the same tired stories we’d been telling for decades and a bunch of crappy low-resolution photos. So, like the youngest kid that I am in a family with four older siblings who used to sit on me and tickle me mercilessly and steal my candy and tell me to go away, I flew to New York and whined to my mom.

“Mo-om,” I groused on the way back to her house from the airport. “Everybody said they liked the idea of this book, but they won’t help.”

“Well, it was your idea, not theirs.”

“And I’m willing to do the lion’s share of the work, but…”

She gave me the No Sniveling Allowed face, the same disinterested expression she’d given me when I complained that we never had potato chips, or that the lady I babysat for paid me with a check again, or that the gym teacher was a lech. So I shut up. Clearly this would be my very own project.

Back at her house that night, with the Yankees game at top volume and my stomach full of New York pizza, I dragged out the old hat boxes full of photos. Lifting their lids released the old musty perfume that said “story.” How many times had we pawed through these photos, listening to Mom tell of how Grandpa arrived at Ellis Island in 1909, of how Grandma worked nights at the munitions factory to help the war effort, of how her neighbors hunted rabbits in the Long Island fields that were now buried by strip malls?

“Hey, Mom!” I shouted over an Ambien commercial, handing her a booklet of old black and white prints. “Who are these people?” I muted the TV and waited for a long story. I poured myself a glass of wine as she flipped through the book with a wistful smile. After all, this was a whole book of photos that chronicled some event from a time back when men wore hats. This would be a good one.

She paused thoughtfully, handed the booklet back to me, and said, “I have no idea.” Her gentleman friend, Jim, unmuted the TV and they returned to the Yankees.

That set the tone for the next two weeks. Clearly I’d waited too long to do this book because at eighty-five, Mom had forgotten plenty, and many of the people who could have supplied the missing information were long dead.

Mom has lived in the same house for nearly sixty years, and many of her friends and neighbors have been there just as long. I made a list of the folks I would interview and began calling and visiting the next day.

As a freelance journalist, I’d interviewed hundreds of people, but nothing had prepared me for this.

“Mom held dance lessons in the basement?”

“Oh sure,” said our neighbor Mrs. Sliwak. “She taught us all. I still remember the fox trot.”

“Mom got drunk and almost fell in the Erie Canal?”

“Well there was this crazy bar in Brockport—” Aunt Cathy began.

“Mom fell asleep during her grad-school classes?”

“All the time!” her teacher friend explained. “She was always exhausted when you kids were little. It was my job to jab her and keep her awake.”

Then there were her bowling pals.

“She’d always get mad that we weren’t more competitive,” our neighbor, Mrs. Vandenheuvel said. “She’d shout, ‘Come on, ladies! Let’s get cracking!’ ”

Then there was Jim, her very-late-in-life love interest.

“She’s so down-to-earth,” he said. “She doesn’t think she’s King Shit.”

I interviewed my siblings (from oldest to youngest, these are Joanna, Ted, Madeline, and Theresa) and their spouses and kids. Some waxed poetic while others had to be prodded, but their responses were always moving.

“I learned to be honest from Mom,” Ted said, “and it pisses me off. I try to be dishonest, but I can’t.”

“One of the things I admire about Mommy is the way she took little things and turned them into big things,” said Joanna. “Even if it was just a five-cent candy after church, she taught us to appreciate it.”

“Nana taught me how to do long division,” said my niece Marianne.

After I interviewed everyone, I added my own core truth: “Mom showed me how to be tough. Whenever I feel defeated or feel sorry for myself, I think of her and I rally.”

My notes filled two legal pads, and frequently made me cry, first in appreciation because Mom’s long life had touched so many people—five kids, eleven grandchildren, three great-grandchildren, nearly two thousand students, countless friends and relatives—but also in sadness because so many people talked about her in the past tense:

“She was always so vivacious.”

“She always had lots of friends.”

“She was always the leader.”

She was still with us, still very much alive, but we all knew she was, well, fading. She’d lost four inches in height, her skin was becoming as gray as her hair, and she was doing old-person things that weren’t so funny anymore. We might have teased her years earlier when she drank from the wine carafe at dinner, or bought a set of candleholders thinking they were juice glasses, or called the fire department because she feared her stove was about to explode (the electric pepper grinder in a nearby cabinet was stuck in the ON position).

But now she was placing her hands beneath the paper towel dispenser and waiting for the water to turn on, setting the table for people who weren’t there, and uttering bizarre non-sequitors such as, “I don’t know why your brother has bricks on his feet.” If I hadn’t already accepted that my dynamo of a mom had truly entered the next phase of her life, namely the holy-shit-how-long-can-she-really-live-alone-what-are-we-gonna-do-now-crap-crap-crap phase, then the contrast being drawn in these interviews between Mom’s former and current selves certainly convinced me.

Interviewing my mom proved the most difficult. She’d never been all that skilled at articulating her feelings—“I feel rotten” was about all we could ever get out of her when she was clearly depressed—and she had no patience for pontification. Combine those tendencies with memory loss, and you get interviews like this:

Me: “What was it really like to be a single mom with five kids—on a teacher’s salary?”

Mom: “It was fun.” (I must have missed that part.) “You kids were good.” (No, we weren’t.)

Me: “What do you hope we’ve learned from you?”

Mom: “Be a good person.”

And while one can present a simple quotation like “Be a good person” as an elixir of truth distilled from hours of introspection, when it stands alone—I mean really alone—it’s a dud.

So I developed a method of first asking others about her life and then plying her with that information. If I led with something like, “Aunt Cathy says you were voted Best Dancer in your senior year. Tell me about your dance partner,” she might talk about why Jimmy De Rosa was such a great guy, and underneath all of that I’d learn what she valued in people: “You could trust him, and he was fun to be with. You could spend an evening with him laughing and dancing and whatnot, but you knew where you stood. Jimmy and I were dance partners, nothing more.”

With coaching like that, I was able to unearth a few other gems:

“Other people plan their lives. I decided early just to take it as it comes.”

“People today expect too much. That’s why they run up their credit cards and get boob jobs and take Viagra. They need to learn to be happy with less.”

“I don’t know how much time I have left. Why should I waste it on people I don’t like?”

Back at Mom’s dining room table, the photo sorting continued. Large piles were separated into smaller piles, and the book grew to forty-eight pages. When my sisters came over they would join in for a while, but I persisted long after they left.

Every day I gathered up artifacts to photograph in the early morning light before harsh shadows ruined the shots—our Christmas music album (the LP was red!), a favorite grease-stained recipe, the worn piano music for Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” that Mom would tackle anew every few years.

In the yard I photographed the hibiscus, the tea roses, and the Montauk daisies Mom nurtured every summer. Then the mailbox, the Ladonia Street sign at the corner, and the “Welcome to Seaford” sign on Merrick Road. I drove around town taking pictures of the pond at Tackapausha, where we used to feed bread ends to the ducks; All American, home of the best burger in town; Wantagh Lanes, the bowling alley where Mom spent countless hours; Jones Beach, which had become its own two-page spread in the book; and many more power spots from our childhood.

I downloaded pictures of S & H green stamps, Jack LaLanne, glass baby bottles, Charles Chips cans, Great Neck High School, Nancy Sinatra, and of course, the Cracker Jacks label from the 1930s because Grandma always bought Mom and Aunt Cathy a box after a day at the beach.

The gathering of photos and information occupied most of my vacation. When I left, I think Mom was glad to see me go. While she was flattered I was doing the book, she was tired of my constant questions and photo-snapping. The attention unnerved her, and it distracted her from weeding her flower beds and complaining about the Red Sox.

Back home in Santa Fe, I set up the book in the layout program InDesign. I typed up my interview notes and organized them by page number. My daughter, Maggie, and I spent days going through our photo albums. I sent more emails and scoured the web for more images.

Then the real work began, which hinged on answering this question: How much truth should the book present?

No one’s childhood is without difficulty, and ours was no exception. Of course there were great times—endless days at the beach, whole-block games of hide and seek, magical Christmas mornings, roller skating in the street, homemade birthday cakes—but Mom was gone a lot. And while she was busy earning her master’s degree, or out on Saturday nights attempting to have a life, her teenagers were home having their own lives. Suffice it to say that we kids navigated what was basically a Lord of the Flies scenario in a working-class suburb—the fight for power, the alliances formed and broken, the competition for scant resources, whether those resources were the last hot dog, the bedroom without the broken window, or our mother’s attention. So how does that play out in print? How should that be reflected in a book meant to honor an elder?

Joanna said to me about fifteen years ago, “Not for nothing, but if I saw your dad lying in the street bleeding, I’d step over him and keep on walking.” Hmm. So should my dad appear in the book? Or do we pretend I just happened along one day in 1964? What about the siblings from my dad’s earlier marriages? What about Mom’s old boyfriend Russ? What about the relatives Mom was never fond of? And what about that giant snorfeling elephant in the room—how was I going to handle her first husband’s death?

The book was meant to be a tribute, to chronicle Mom’s life and make her happy. But all of life is not happy. Treachery and disappointment worm their way into so many unsuspecting families, and that was true of us as well. But while various truths had found their way to the surface decades earlier—and I had exposed many of them myself—here I was eager to showcase the good. Was I nuts?

And who was I to be telling this story, anyway? Sure, I’m a writer, an English teacher, and a yearbook adviser—I had the skills—but did I have the cred? After all, I’m only a half-sibling, and because I’m the youngest, I lack the memories of the earliest years. Did that mean I had a unique perspective, a more objective point of view? Or did that mean I was not only ignorant, but also presumptuous? What if I got the story wrong? What if Mom hated the book because I whitewashed the bad times? What if she hated it because I didn’t?

One morning in early July, after I’d spent most of the night staring at the ceiling, my husband, Scott, casually said, “You know, after you finish the book and everyone has a copy, they’ll probably never even look at those old hat boxes of photos again. The book will become the canon; it will become THE story of the family.”

I pushed my coffee away and dropped my head to the table. He was right. And I was more trapped than ever. I couldn’t abandon the project at that point, yet I didn’t know how to proceed. To make matters worse, my mother’s weakening faculties made it all the more urgent that I finish the book quickly. I had initially told the family I would have the first draft done by August and a final copy for Mom by Christmas.

“That might be too late, Boo,” Madeline warned. “She could be one more mini-stroke away from not appreciating it at all.”

Scott refreshed my coffee, toasted us a bagel, and sat down across from me. “Hey,” he said, nudging my shoulder. “Who’s your audience?” As a marketing dude, Scott is adept at identifying and reaching specific audiences. “Come on,” he said, nudging me harder. “Who’s your audience?”

“Everyone,” I moaned. “The whole family. Maybe the whole world.”

“No,” he said. “It’s your mom. You have an audience of one, and you know that audience very well. That’s all you have to think about. Make every decision with your audience in mind. Come on. Just get started.”

So I did.

And it was an amazing experience.

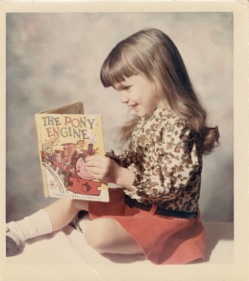

The magic started with the scanning of photos. While turning a printed photo taken yesterday into a digital file is a ho-hum task, one you can do while reading a magazine as the machine whirs along, scanning a decades-old black and white photo is quite a different experience. First, picture my mom’s kindergarten class photo: 8 by 10 inches with thirty kids in four rows. Mom, sitting with hands clasped in a plaid dress and white anklets, measures about an inch and a half. But when I scan the photo at high resolution, the image fills the screen. Adjust the brightness and contrast, and there she is, in all her long lost little-girlness. In print, she’s just a dot among other washed-out dots. But now here she is, with her serious face and polished shoes, so much larger and more vivid than the print. I do the same for her other class pictures and scroll through them in wonder. Since the Great Depression, these photos have been keeping tremendous secrets, but now those secrets are out. Look at Mom’s sad dark eyes and swarthy complexion, in contrast with her self-assured, waspy classmates. (Mom grew up in Great Neck, on the north shore of Long Island, where Grandpa tended gardens on huge, Gatsby-like estates; these kids’ parents owned those estates.) Look at the starched collar, the carefully styled hair—Grandma made sure Mom was just as clean and shiny as the other kids.

The same miracle occurs for every ancient, faded photo I scan. Small, indistinct faces, long diffused in some sort of Kodak ether, suddenly coalesce, regaining their form and clarity. A glowing smile, a baby’s scowl, a thoughtful glance—they all reappear, often larger than life on the screen. Although I have for years railed against how Photoshop manipulates reality in today’s media, here I am experiencing its magic as I reclaim these images. The irony is not lost on me as I manipulate the past, removing a blemish here, restoring color balance there.

Not only do faces crystallize, but items in the background also appear. Wallpaper patterns, toys, trophies, baby formula, tiny shoes, framed certificates, tea cups, magazines, cigarette packs, fishing poles, dashboards, loaves of bread, TV knobs, Spic ’n Span—so many things that have been too small, fuzzy, or faded to detect in these old photos are suddenly clear. I can magnify the view so much that I can almost read the headline on The New York Times my grandpa is reading in 1956, and can tell that the item on the table next to him is a hinged frame with college graduation photos of my mom and my aunt. I can even discern the lace pattern on the curtains behind him.

As I work, I stream Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey on YouTube and fall into the dream of the past. I watch in constant wonder as images take form on my screen: Mom and her first husband, “Big Ted,” drape tinsel on a Christmas tree. My brother, “Little Ted,” grips the steering wheel on the family’s small boat. Baby Madeline dozes in a highchair. Joanna helps Mom mop the kitchen floor. Theresa grins with bits of teething biscuit smeared on her tiny face. Grandpa carves the Thanksgiving turkey. Grandma serves up spaghetti for Sunday dinner. Mom looks up from her teacher’s desk. Big Ted stands next to Uncle Chet at a picnic, bottles of Rhinegold in hand, laughing. There’s Ladonia Street back when today’s towering oaks were so small they needed to be staked. In these snapshots of the past everyone is happy. Everyone has nothing but hope for the future. Everyone is still alive.

The phone rings, interrupting my reverie. It’s Mom, calling to tell me I forgot “some phone thing” at her house. It takes me a minute to adjust to her shaky voice—I expect her to be twenty-nine. I figure out from her description that I left a flashdrive behind.

“No big, Mom. How are you?”

“The Yankees are winning.”

“Who’s your favorite Yankee of all time?” I click on the photo of her standing next to Joe DiMaggio at the wax museum.

“Joe DiMaggio.”

Yes!

“And today?” I find the photo of Derek Jeter I downloaded earlier that day. There he is defying gravity, caught mid-air as he leaps over a runner who is sliding into second base. His handsome, earnest face is fixed in intensity.

“Jeter, of course.”

Yes! I love Jeter. I love my mom. I can’t wait till I get to the baseball page.

“How’s the book?” she asks.

“Great!”

Several of the issues I’d worried about have resolved themselves. A neighbor, bless her heart, remembers my dad well, so I have one positive quotation to include with a picture of him. I decide to put all the many old stories, anecdotes, and private jokes into quiz form, which allows me to showcase my mom’s personality and to include her younger voice—the one that never shook while we were growing up.

Here is quiz item #23:

When Mom doesn’t like what someone is saying, or regards that person as an annoyance, what is she likely to say?

a. “Go fly a kite.”

b. “You’re full of beans.”

c. “Go shit in your hat.”

d. “Go play in traffic.”

e. “Take a long walk off a short pier.”

f. “Dry up and blow away.”

g. All of the above.

You guessed it—the answer is “g.”

I work ten hours a day on the book, which has grown to sixty pages. Summer storms drench the world as the voices of Ella Fitzgerald and Frank Sinatra blend with the pelting rain. It’s hard to pull away to swim laps, make dinner, or spend time with my own kids, Nick, twenty, and Maggie, fourteen.

I finish the early years and skip ahead to the spreads about Mom’s travels, the beach, bowling, gardening, teaching, and the extended family. I set up a two-page spread for each of my siblings and their families, creating individual timelines. I call Great Aunt Nancy and Aunt Cathy continually to fill in information. I scan old drawings and cards we made for Mom. (“Dear Mommy, I love you you are a very nice cook. You are a woaman Who is Nice.”) I’m on a roll now, and I am certifiably the best daughter in the world.

But that snorfeling elephant is demanding my attention.

By late July, I know I can’t put it off any longer. The book is nearly done, but the pages dedicated to Big Ted’s death and the year following it are blank. I don’t want to work on those pages. I don’t want to leave behind the children’s merry faces, my vibrant mom, or the little pool where Big Ted smiles, kids clamoring over him as he relaxes after a day of work at the school where he was principal. Everything is as it should be. No one knows what’s coming, and I don’t want them to know. If I never finish the book, maybe they never will. Why can’t Tommy Dorsey keep playing? Why can’t my mom keep dancing? Why can’t the kids keep beaming in their safe, loving, intact family?

I remember how as a kid these pictures always looked so right to me, and the ones with my dad always looked so wrong. Theirs were the golden years; mine were brass. I recall how as a child I used to passionately tell my mom I would give up my life if it would bring Big Ted back. She would tell me she would have had a fifth kid anyway, that I would have come along even if Big Ted hadn’t died, so I could quit making that gruesome offer.

I step away from the desk, fighting tears. My chest hurts, filled with a heavy, tightening dread that makes it hard to breathe. It’s as if I’m leaving a loved one’s bedside after the doctor has said, “It’s only a matter of time.” And I’m somehow responsible for the patient’s death.

I lie down on the couch and watch an aspen sway in the breeze. Leaves rustle. Birds sing. I sleep. When I wake, I instantly remember what I’d been thinking before I fell asleep: He’s not even your dad.

I watch the aspens again.

No, he’s not my dad, but this is my family, and this story has been so big and so sad for so long that it has shaped everything. In my twenties, when I was more prone to New Age dogma, I used to believe everything happened for a reason, and that hard times were to be seen as gifts because they helped us find strength we didn’t know we had.

What a load of crap.

Big Ted’s death was a mistake, pure and simple. He went into the hospital because he’d been feeling weak—he had a heart condition—and soon he contracted a staph infection and died. Someone hadn’t washed his hands properly, or a janitor hadn’t use the right amount of disinfectant on the floor. That’s why my siblings lost their sweet father and my mom lost her beloved husband. It was a mistake.

Then there’s the issue of my dad himself. At sixteen years older than my mom (he was closer to my grandparents’ ages than hers), with his despised last name (he legally adopted the four kids), his son who lived with us (himself mourning the death of his own mother), his drinking (scotch), and his explosive anger (watch out!), he would be poison for the unwitting family who are still smiling on page nine of the book. How I wish I could direct my cursor to the Edit menu, select Delete, and spare them all that fate.

Was I a mistake?

As a kid, once I accepted that I couldn’t die to bring Big Ted back, I directed my energy toward wishing my mom would at least not have married my dad. Then she could have lived her life as a noble widow, with her young family unsullied by an outsider. There would have been no strangely spelled Dutch surname to supplant the Italian name, no capricious punishments from the erratic stepdad, no raging maniac to impel us to take shelter at Aunt Cathy’s house.

And after the divorce there would have been no Sunday visits for my dad and me, the ninety minutes of polite torture we endured week after week for years and years.

Dad: “Would you like to play Mankala?”

Me: “OK.”

Dad: “Would you like to go to the pet shop?”

Me: “OK.”

Dad: “Would you like to visit Aunt Rita and Uncle Jim?”

Me: “OK.” (Rita and Jim were my godparents. One Sunday when we dropped in on them unannounced, they were cleaning up after a party and she had a massive black eye.)

As I stare at the swaying aspen, I recognize the peculiar guilt I have felt my whole life. Faulty causation is what it is, a logical fallacy that I dutifully teach my students to recognize every year: post hoc ergo proctor hoc—after this, therefore, because of this. My existence didn’t cause Big Ted’s death; it happened six years before I was born. And it wasn’t my fault that my parents rushed into marriage when they were both still mourning their late spouses.

“Barbara’s so spoiled she even has her own father.”

How many times did I hear that as a kid?

And here I am agonizing about how to portray Big Ted’s death. Tell me again why I took this on?

I approach my computer the next day as if attending a funeral. I’ve saved two photos for this page—one of Big Ted in a sailor suit when he was about four years old, and one at thirty in a suit with a bow tie, looking both kind-hearted and handsome. I search my interview notes about him and sob as I format the text.

“Tell me about Ted,” I had asked everyone who knew him.

“He was a great guy,” Great Aunt Nancy said. “Your mother was so happy with him.”

“He was very good to your mother,” said Aunt Cathy. “Grandma and Grandpa thought he was fantastic.”

“He was a wonderful family man,” said Mrs. Vandenheuvel.

“Talk to me about your dad,” I had said to my siblings.

Theresa, as the youngest, never knew her dad, but she thinks about him every day. “I don’t think anyone in this world ever made Mommy smile like he did,” she said, choking up. “He touched so many people.”

“Daddy has my back,” Madeline said, as she has always said. A narrowly avoided car accident, a favorable job review, her daughter’s recovery from cancer—Madeline has always believed her dad is her guardian angel.

The older kids have some actual memories of him.

“All I remember is being on the boat,” Ted said. “I remember throwing my baloney overboard and eating the bread, and I think Mom was mad at me for it.” He added, “I grew up without a father. That’s why I’m so close to my kids.”

Joanna said, “I remember he had a green boat and he had a little fishing pole for me, but all I caught was seaweed. Teddy had a captain’s hat and Daddy would set him in the captain’s seat and Madeline was in a stroller.”

Although Joanna’s memories of her father are often envied, she also has the dubious honor of remembering his death: “When my father died, Mom said that Daddy wouldn’t be coming home, that he went to Heaven. I asked why and she said, ‘God needed a really good principal in Heaven and Daddy was the best, so God took him.’ I accepted it…. It made perfect sense in my four-year-old world.”

She also remembers, the following Christmas, making her dad a pencil box out of an orange-juice can that she painted and decorated. When she brought the gift home from school, she asked Mom how she could get it to him: “Mom said when Santa Claus came, he would take the gift to Heaven for Daddy‘s desk.”

I sob as I work on this page and no amount of big band swing makes it any better. Finally, I settle on a simple layout: The bow-tie photo takes the right half of the page, with birth and death dates below. Quotations fill the left half, with the sailor-suit photo on the bottom. Done.

I go for a swim, hoping to release my sadness into the water. But in the quiet of the pool’s deep end I begin to wonder, What is this book about, anyway? Is it about Mom and her life, or is it about me? Or, more specifically, about Big Ted and me? Am I chronicling my mom’s life, or am I trying to write myself into the family? I don’t have an answer.

I leave the pool, return to my computer, and push through to the following spread. I tear up again as I write the headline “A New Chapter,” which is how Mom always labeled the time after Big Ted’s death. One picture shows baby Theresa lying on a rug as a cousin stares at her blankly. Three-year-old Ted looks desolate. The rest are pictures of my grandparents on our old couch with kids sitting all over them. Evidently they helped out a lot during that time, and Mom avoided the camera. On the next page, I finally show up, along with five square inches about my dad. And life goes on.

This is enough reality for my audience of one. And enough for me, too. I take a break from the book for a few days.

When I return to it, I feel lighter, and I focus on the quiz. I laugh out loud as I sneak inside jokes and family trivia into fifty multiple-choice, fill-in-the-blank, and matching questions. I laugh at Mom’s spunk and at the mishaps and idiosyncrasies that make up every family. I write up long-winded, snarky explanations in the answer key and snicker some more. It’s a hoot, that quiz. I still laugh when I read it.

My sisters made only minor changes to the first draft, and I designed a simple cover—a huge photo of a hibiscus blossom with Mom’s name across the petals: Madeline Abbene. It’s a beautiful book.

I mailed Mom her copy a week before Thanksgiving. I was sorry I couldn’t be there for the unveiling, but the phone call was pretty gratifying.

“I can’t believe you did this!” Mom said over and over. “It’s more than I ever imagined! I can’t believe you did this!”

“I hope you like it, Mom.”

“Like it? I love it! My goodness! I don’t know what to say!”

“I love you, Mom.”

“I love you, too, dolly. Thank you so much.”

“You’re welcome. Mom. Thank you. For everything.”

I like to think the book made Mom feel loved and appreciated. I like to think that when she looks back at her life, the joys and satisfaction will outweigh the pain and trouble.

In creating the book I had the opportunity to see my story anew. Yes, I told the story with more emphasis on the good than the bad. But isn’t that how it should be? And isn’t that how it truly was?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed