No, the point I wish to make here is much more nuanced, more rarefied: I went bra shopping last week, and it sucked.

First, the Intimate Apparel section—like a REM-state stress dream that lasts till lunch—is a study in extreme market segmentation, a million square feet of mysterious-yet-boring garments on tiny, clacking hangers. There are 36,365 females in Santa Fe (I looked it up), and I’m pretty sure that Kohl’s stocks a different bra for each one (possibly even the infant girls). Maybe if your weight hasn’t changed (mine has, thanks for pointing that out), or you’re one of those women who actually has a favorite brand (who could know?), or you can still read the label on the tattered specimen you’ve been wearing for ten years (right), your shopping trip will be a breeze (I hate you). But for me? After at least fifty try-ons and two hours of my life that I’ll never get back, I left with two overengineered, overpriced bras that I already hate.

Allow me to share with you the world of bras from the perspective of a woman of a certain age.

Your first task is to rule out the ones with “cutlet” inserts or pushup padding, bras marketed as “Love the Lift,” “Ego Boost,” and the like. When I was in high school, a girl suspected of wearing “falsies” was the target of eye rolls, but falsies are everywhere now. Speaking of high school, it’s best to avoid the Juniors section altogether. First, it’s full of miniature, mango-magenta bras sold in three-packs that you cannot—repeat, cannot—wear after two kids and a mortgage. Second, it’s full of teen-age girls. Now as a high school teacher I love teen-age girls, but in the phantasmagorical world of Juniors bras, they are a terror. The same way you’ve already squeezed the cups and declared half of their merchandise categorically unfit, they’ve done the same in your Misses section, smugly snickering at the giant, matronly devices you’re about to try on. So. Just. Stay. Away.

OK, on to Misses. Let’s get this done.

Say, this looks sensible: beige, smooth-ish, simple. My size must be here somewhere. Clack, clack, clack. This one, no this one, no this one, no this one—there! Well, there’s the band size, but not the cup. Wait, there’s the cup size, but not the band. Wait, there’s the—oh, it’s a different style now. Clack, clack, clack.

Here’s the style, but this one’s white. No, it’s different. Wait, where did the first one go? Clack, clack, clack. Fine, this will work. Wait, there’s my size, but this one’s black. Clack, clack, clack. OK, the black will do.

How about this one with the front-close contour? Way at the back, there’s my size. Clack, clack, clack. Oops, knocked four on the floor. How about a wire-free lift? Clack, clack, clack. T-front? Clack, clack, clack. Racerback? Clack, clack, clack. Plunge? Balconette? Convertible? Compression? Molded? Halter? Moisture wicking? Clack, clack, clack.

I have three viable options after twenty minutes. Not bad.

OK, find the fitting room, try on the first one, and…

FOR THE LOVE OF GOD, WHAT IS THIS THING? Shiny weirdness! Spillage! Strangulation!

AND WHO IS THAT MIDDLE-AGED WOMAN IN THE MIRROR? This isn’t even my size anymore! Oh, the humanity….

Back to the racks, clack, clack, clack. Back to the fitting room, cringe, cringe, cringe.

Perhaps an underwire… Rebar! Get it off!

Or no underwire… Rubber band! Get it off!

Maybe this lacy one… Scratchy! Get it off!

Or the fully lined… Scary mannequin! Get it off!

Barely there… Back fat! Get it off!

Full coverage… Body armor! Get it off!

Breast petals… Nipple hats! Get it off!

Comfort devotion… Uniboob! Get it off!

Lined cup, demi cup, soft cup, seamed cup…clack, clack, clack.

Line up, debit card, find the car, slump home…mope, mope, mope.

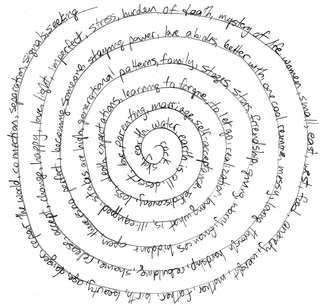

You know, just because Danté never wrote about the Intimate Apparel Circle of Hell doesn’t mean it isn’t real. What’s also real is that I hail from a bra-hating matriarch who taught me better. What I really should be doing at 8 o’clock on a Monday evening is unharnessing the girls, pouring a glass of wine, and enjoying my life. And that’s right where I’m headed right now.…

RSS Feed

RSS Feed