Over the seven years it took me to write the book—through planning, drafting, readings by friends, editing, and even the proofreading process—the book had no name. It remained title-free until 24 hours before it was sent to the printer.

At first this lack of a title had a groovy, breezy quality. I bopped along assured that I would hit upon the title any day, that it would come unbidden, trailing clouds of glory and all that. But after expecting that blessed state to arrive for the better part of a decade, I somehow accepted that maybe, just maybe, I would have to try something different.

First I brainstormed alone, tapping out notes on my iPhone any chance I got, composing prodigious lists of terrible ideas. Then I took the least terrible of those ideas and tormented my friends with group texts, asking which might entice them to pick up the book, what the titles made them think of. (Hey, uh, sorry about all that. . . .) Then, just as I would finish tabulating their responses, I’d decide I hated all those ideas anyway and start over.

Next I decided to share the love and torment my editor as well. Marty would trudge through the door, I’d hand him a glass of wine, he’d eye me sternly and say, “Today,” and I would promise, “Yes, today.” By the end of each meeting I’d feel sure we’d nailed it, and for hours after I’d triumphantly proclaim the title aloud over and over, the way teen girls used to place their crush’s last name after their own, imagining it as their married name. (Yes, I did that as a teen.) But then I’d wake up the next day and think “Yuck,” as if I’d spied that cute guy picking his nose on the bus. And I would be decidedly single again.

This went on. And on. As the deadline loomed (I wanted to get an advance copy to my mom for Christmas), I became truly panicked. And I felt really, really stupid.

In early December, my dear friend Sheri Sinclair—embattled by my endless texts—sent me some ideas for creative exercises I might do to spark my title-process-turned-angst in a new way. Of course the jaded English teacher in me thought, “Oh, please, I’ve seen all these gimmicks before.” But I was desperate, so I tried them.

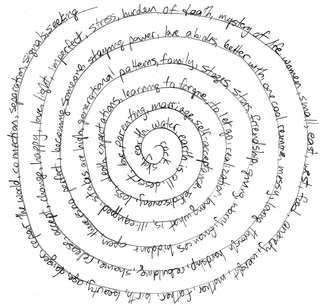

First I did a free-association bubble thingie. No joy there. Then I turned my main idea into a poem—fun, but no great shakes. Next I drew a spiral on a sheet of paper. Writing from the center outward, I filled the spiral with words and ideas associated with the book.

I kept writing, turning the page until the spiral was full. Then I looked to see how random words aligned from one ring to the next. As if the spiral were a clock face, I looked at the words stacked up on the hourly “wedges” of one o’clock, two o’clock, and so on. “You might get some poetic combinations,” my kind-hearted and ever-supportive friend had said.

And whaddya know? There it was. Stacked up on the nine o’clock wedge were, among others, the words “love,” “death,” “perfect,” and “world.” Hmm

. . . as Bugs Bunny once said, now we were cookin’ with gas.

I connected the words in a phrase on a new sheet of paper, looked away, and looked back. Made a cup of coffee and returned to the words. Went for a walk and returned to the words. Blasted some music and returned to the words. No, this was not a crush, not a date, not even a bestie. This was the one.

Such ordinary words. (I had liked the idea of a weird title, with a word that might hook itself like a curious barb in a reader’s mind.) No place names. (I had expected the title to reflect the book’s setting—Joshua Tree National Park, Twentynine Palms, Santa Fe.) No sensory words. (I had especially clung to the idea of using words one could see, hear, touch, or taste.) But this was it.

Love and death in a perfect world: The words rolled off the tongue. In iambic tetrameter, even. It featured no strange spellings, no intricate punctuation, no unconventional capitalization. A title ordinary in every way, yet grandiose in scope. Who could ask for more?

I loved it and the thing was done: my book’s last—and first—seven words.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed